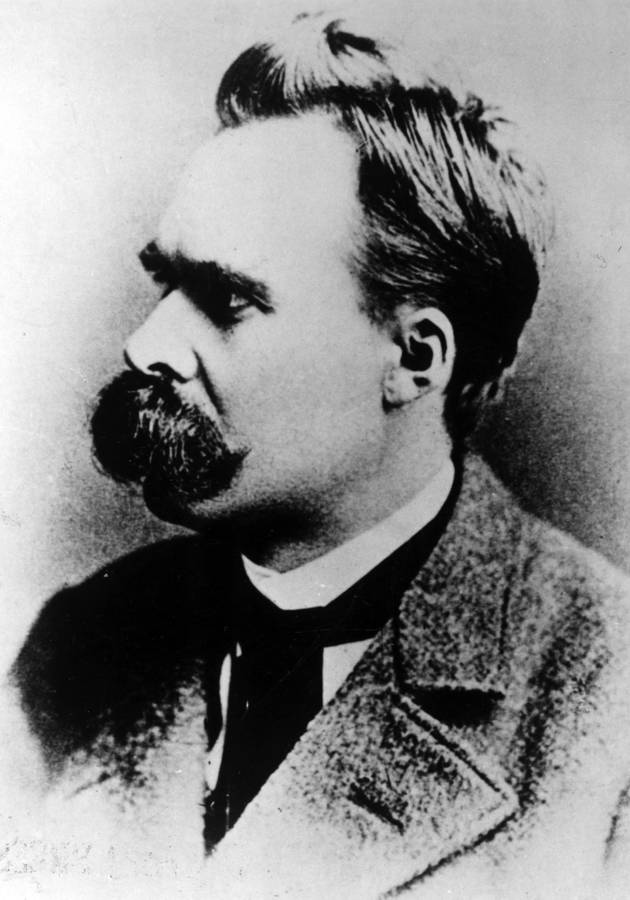

Anointed, with Marx and Freud, as one of the three masters of suspicion, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche foresaw the coming of a new, godless age after Darwin and – in works of hauntingly beautiful prose and poetry – struggled to convince his contemporaries to embrace its imminent arrival. Join us as we follow his life journey and the evolution of his powerful ideas.

Grounded in Judeo-Christian values: Nietzsche’s childhood

Nietzsche was born on October 15, 1844, in Röcken, a small village in Saxony, on the 49th birthday of Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia and named after the king by his father Carl Ludwig, a Lutheran pastor. Both of his grandfathers were Lutheran ministers as well, and it was expected from him to follow in their footsteps. However, Nietzsche’s belief in God’s benevolence was shaken early on, since his father died a few months before Nietzsche turned 5, and his baby brother died the following year as well.

Soon after, his mother moved the family to the much larger town of Naumburg, where Nietzsche was raised religiously in a household of women – his mother, maternal grandmother, two paternal aunts, and a younger sister, Elisabeth.

An excellent student, Nietzsche won a scholarship to Pforta, the most prestigious boarding school in Germany. He graduated in 1864 after receiving a thorough training in the classics and getting the highest grades in religion and German. After graduation, still hoping to become a minister, he registered as a theology student at the University of Bonn. However, after the first semester, he lost his faith in God entirely.

In a letter sent in June 1865, Nietzsche wrote to his pious sister Elisabeth the following: “If you wish to achieve peace of mind and happiness, have faith; if you wish to be a disciple of truth, then search.” At the age of 20, Nietzsche decided that he didn’t want the false peace of mind that religion offers and vowed to become an explorer and a devotee of truth, no matter where this might lead him.

Putting Nietzsche into context: Feuerbach, Darwin, Strauss

To better understand Nietzsche’s transformation, some context seems necessary. Three years before Nietzsche’s birth, a German philosopher by the name of Ludwig Feuerbach published a curious little book titled “The Essence of Christianity,” in which he argued that God is merely an external projection of man’s inward nature. “God did not, as the Bible says, make man in his image,” Feuerbach wrote, “but on the contrary […] man made God in his image.” In 1859, Darwin’s “Origin of Species” introduced the world to evolution, a scientific theory that elegantly explained the complexity of the world while removing the necessity of a creator deity. Just two years later – and four years before Nietzsche’s letter to his sister – German liberal theologian David Strauss wrote a controversial biography of the “historical Christ,” titled “The Life of Jesus.” In it, he denied Jesus his divine nature and dismissed his miracles as late mythical additions unfounded in factual history.

Nietzsche carefully read and – like many other thinkers of his age – was profoundly influenced by all three of these works. However, he was arguably the first to understand the severity of their discoveries, the first to see that casting doubt on the existence of God wasn’t only a theological issue – but an act destined to disturb the very foundation of Western civilization.

For millennia, people didn’t need to tell apart good from bad and right from wrong: the Bible did it for them. But by the second half of the 19th century, scientists had accumulated enough evidence to thoroughly question its validity as a moral benchmark. “Who should now decide what is good and what is bad?” – the young Nietzsche wondered. What would fill the moral void left by the discrediting of the Christian God? Could this be a chance for humanity to revert to an alternative “holy book,” one not as restraining and life-negating as The New Testament? Nietzsche spent the third decade of his life trying to find an answer to these difficult questions.

Richard Wagner, Nietzsche’s surrogate father

After stopping his theological studies, Nietzsche registered at the University of Leipzig as a student of classical philology under noted classical scholar Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl. He was such an outstanding student that, in 1869, at the recommendation of Ritschl – who described him as a “phenomenon” and “idol of the younger generations” – he was appointed to a professorship at the University of Basel, Switzerland, with merely 24 years of age and an unfinished doctoral dissertation. To this day, he remains the youngest to ever hold the university’s chair of classical philology.

The appointment came as a surprise to Nietzsche, since he considered giving up philology for science at the time. More importantly, by then he had already become part of the inner circle of Richard Wagner, a larger-than-life German composer of operas. His revolutionary ideas on art and culture had captured Nietzsche’s imagination to such an extent that the musician was quickly replacing Ritschl as an intellectual father figure. During the following two years, Nietzsche would become convinced that Wagner’s bloody, all-inclusive, and heavily-orchestrated operas were a much necessary and decisive step toward the rejuvenation of humanity in this post-Darwinian, post-Christian world.

Dismantling Apollonian culture: the resurrection of Dionysus

Published in 1872, Nietzsche’s first book, “The Birth of Tragedy,” elucidates the need and nature of this cultural renewal. Highly speculative, the book offers a new theory of art and seeks to frame Wagnerian opera as a way to recuperate what European culture had lost since the demise of ancient Greek tragedy: high-spirited cheerfulness in defiance of death and the “metaphysical consolation” of thinking about life as something “indestructibly powerful and pleasurable.”

In Nietzsche’s opinion, the ancient Greeks were aware of the randomness and absurdity of life, and their myths and tragedies were their way to embrace this fact. “Life may be cruel and destructive,” they reasoned, “but art is eternal and the human spirit unbreakable.” Unwilling to accept death as part of life, early Christians cowardly retreated in an ideology that postulated the existence of another world, one devoid of misery and loss.

To explain this better, in the book, Nietzsche introduces the famous distinction between the Apollonian and Dionysian forces of nature, named that way after the Greek gods of the sun and the wine. In his interpretation, Apollonian forces are the ones governed by reason – individuating and final, they attempt to give form to the chaos of existence through clean and beautiful illusions. Dionysian forces, on the other hand, are wild and emotional – they symbolize the primal unity of all things in an endless state of becoming, as well as the sensual world of ecstatic frenzy.

Early Greek tragedy – as exemplified by Aeschylus and Sophocles – was capable of fusing Dionysian joy and Apollonian illusion. But then Plato and Euripides dissociated the two and banished Dionysus from art and life, celebrating reason and promoting illusory salvation; the New Testament merely followed suit.

While early ancient Greeks joyfully affirmed life in the face of death, swayed by Plato and his followers, Christians started dreaming of being compensated for the agony of life after dying. The more painful their earthly existence, the more likely they were to be rewarded in heaven. In his 20s, Nietzsche grew to believe that – after two millennia of Christian asceticism – the life-affirming presence of Dionysus could once again be felt in Wagner’s operas. He was now loudly shouting from the rooftops: the Christian God is dead – long live Dionysus!

“Whither is God? We have killed him – you and I”

“The Birth of Tragedy” was ill-received by German scholars and all but destroyed Nietzsche’s professional standing as an academic philologist. To make matters worse, in his subsequent operas, Wagner turned to Christianity, anti-Semitism, and German nationalism – three things Nietzsche came to loathe. The inevitable break between the two came around 1876.

Just three years later, Nietzsche’s professional career came to a premature end: severe health problems drove him to resign his chair at Basel at the age of 34. The university gave him a modest pension, which he used to begin a ten-year period of wandering across Europe in search of a suitable climate for his condition. Nothing helped: with each passing year, his debilitating migraines grew more intense, and his eyesight got worse.

Even so, before suffering a total mental breakdown in 1889, Nietzsche managed to write ten substantial books, in which he further developed his already provocative ideas. The first of these books was “Human, All Too Human,” Nietzsche’s first great statement of individualism. Subtitled “A Book for Free Spirits” and written in short aphoristic bursts (which would become his trademark), the volume publicly announced the philosopher’s break with Wagner and challenged mankind to start thinking for itself. Four years later, in “The Gay Science” – the most personal of Nietzsche’s books – the philosopher made the final step, announcing, in no unclear terms, the death of God and the end of traditional morality.

In the 125th of the book’s 383 aphorisms, a madman seeks God with a lantern in the bright morning hours of the day. “Whither is God?” he repeatedly asks the people at the marketplace but is mockingly laughed off by them. “I will tell you,” he suddenly cries, “we have killed him – you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? […] How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? […] Who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it? There has never been a greater deed; and whoever is born after us – for the sake of this deed he will belong to a higher history than all history hitherto.”

Zarathustra descends: “I will teach you the Overman!”

Nietzsche’s cry was loud and clear: now that scientists had disproved the existence of God, humankind was free from its religious shackles, and able, for the first time in history, to experience absolute freedom. In a world without a celestial overseer, nothing could be inherently good or evil – people were left to decide this for themselves. It was time for humans to step out of God’s shadow and become gods themselves. It was also time for Nietzsche to show them the way out and erect for them “a new image and ideal of the free spirit”: the Overman.

He introduced the concept of the Overman in “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” a book he didn’t shy away from later describing as “the greatest gift” ever given to humanity. In it, a prophet named Zarathustra, having lived a decade of wisdom-weary solitude at the top of a mountain, decides to climb down and share his findings with the rest of humankind. Evoking Darwin, he tells a gathered crowd that the “human being is something that must be overcome.” “What is the ape to man?” he asks them. “A laughing stock or a painful embarrassment. And that is precisely what the human shall be to the Overman.”

The Overman, for Nietzsche, is the next stage of human evolution. He is “the meaning of our world,” just like the soon-to-be displaced religious man was always “the meaning of the other world.” Promising illusory afterlife, Christian morality had perverted for humans all bodily functions with guilt and fear and condemned self-assertion as pride.

By turning this morality on its head – that is, by embracing and affirming the values of this world and our physical bodies – man could now evolve into the Overman. “I beseech you, my brothers,” shouts Zarathustra, “remain faithful to this world, and do not believe those who speak to you of otherworldly hopes! They are mixers of poisons, whether they know it or not. They are despisers of life, dying off and self-poisoned, of whom the earth is weary: so, let them fade away!”

Transvaluation of all values in a world of multiple truths

Contrary to popular opinion, Nietzsche’s call for “transvaluation of all values” wasn’t nihilistic, but life-affirming. He believed that the idea of God was the reason for much human suffering, and he blamed everyone supporting religion for pushing humans to renounce their life here on earth – the only thing they have – for something that might never come. In this sense, far more than a nihilist, Nietzsche was a precursor of existentialism, a 20th-century philosophical movement, which claims that human life has no intrinsic meaning except the one created by humans themselves.

In his subsequent books – “Beyond Good and Evil,” “On the Genealogy of Morals,” and “The Antichrist” – Nietzsche’s critique of Christianity and all moral philosophers of the past grew even more violent. He presented himself as the pinnacle of the old age and a herald of a new one. He made a case that all thinkers before him had been narrow-minded and shortsighted because they wanted to supply a rational foundation for morality and failed to see that they were only giving excuses for the dominant morality of their age. In reality, there were always as many moralities as cultures and people because there was never a single, transcendental truth – merely different interpretations and perspectives of life.

As earth-shattering as this might sound, Nietzsche insisted that his discovery wasn’t apocalyptic, but liberating. The death of God didn’t make life meaningless, but it actually gave life meaning – by finally granting humans the freedom to invent it for themselves. Through Nietzsche, self-making and self-mastery first became a morally legitimate way of life. Previously thought of as prideful because of religion, these two soon became coveted virtues and strived-for qualities. They still are.

“Have I been understood? – Dionysus against the Crucified One...”

On the morning of January 3, 1889, upon leaving his house in Turin, Nietzsche witnessed a coachman viciously flogging his horse at the other end of Piazza Carlo Alberto. Shocked by the man’s unmotivated cruelty, he ran to stop him. However, once he got close, all that he could do was to embrace the horse, tears streaming down his face. A few moments later, he collapsed. When he regained consciousness, his sanity was gone.

In the days following this event, Nietzsche dashed off several occasionally lucid and beautiful, but ultimately wild and bizarre letters to various correspondents, including Wagner’s wife Cosima and some of his earliest admirers, such as Swedish writer August Strindberg and Danish philosopher Georg Brandes. Proclaiming his own divinity and advocating for the deaths of the German emperor, the pope, and all anti-Semites, these were clearly not the writings of a sane individual.

Some of the letters were signed “Dionysus,” while others “The Crucified.” It is difficult to avoid the speculation that this final polarity not only marked Nietzsche’s split from Christianity early in his life but, in some inscrutable way, also marked an irreparable split with himself.

“My time has not yet come”

Nietzsche spent the last 11 years of his life in a near-vegetative state, sinking further and further from the real world until his death on August 25, 1900. “My time has not yet come: some are born posthumously,” he wrote in his last original book, the autobiographical “Ecce homo,” not long before descending into madness. In the book’s concluding chapter, immodestly titled “Why I am a Destiny,” he pronounced something even more self-appreciative: “I know my fate. Some day my name will be linked to the memory of something monstrous, of a crisis as yet unprecedented on Earth, the most profound collision of consciences, a decision conjured up against everything hitherto believed, demanded, hallowed. I am not a man, I am dynamite.”

Originally mistaken for the exasperated ravings of a soon-to-be lunatic, more than a hundred years later, these remarks appear more than just prophetic. At the beginning of the 21st century, it is difficult to think of a philosopher whose influence on modern culture exceeds Nietzsche’s. His words and ideas detonated an explosion on the premises of moral history, sending shockwaves through time and space. Our modern world still reverberates with their power.

Sources

Works by Nietzsche

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science [translated by Walter Kaufmann] (New York: Vintage, 1974).

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy [translated by Douglas Smith] (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil [translated by Judith Norman] (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra [translated by Adrian del Caro] (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo [translated by Duncan Large] (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Main biographical

- Alan D. Schrift, “Nietzsche, Friedrich,” Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol. VI [Donald M. Borchert, ed.] (Gale, 2006), pp. 607-617.

- Walter Kaufmann, “Nietzsche, Friedrich (1844-1900),” The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy [Jonathan Rée and J. O. Urmson, eds.] (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), pp. 267-270.

- “Nietzsche: Beyond Good and Evil,” Human, All Too Human (BBC2, 1999).

Other and contextual

- “Friedrich Nietzsche,” in Encyclopedia of World Biography, Vol. Xi [Paula K. Byers, Suzanne M. Bourgoin, and Neil E. Walker, eds.] (Gale, 1998), pp. 390-392.

- “Friedrich Nietzsche: Man Is Something to Be Surpassed,” The Philosophy Book (New York: DK, 2011), pp. 214-221.

- Jörg Salaquarda, “Nietzsche and the Judaeo-Christian tradition,” The Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp. 90-119.